Music Theory For Guitar and Harmonica

Learn your instrument faster. Learn a second instrument faster. Gain Confidence. Match the notes on the harmonica to the notes in chords for awesome solos.

Lesson Info

Lesson Length: 23:42

Instructor: George Goodman

Concepts:

This is the meat and potatoes lesson where you learn about

* Pitches and how they are named

* Major Scale

* Intervals

* Music Notation and the Musical Staff

* Circle of Fourths and Fifths

* Key Signature

* Harmonica Positions

Recommended Gear

Takamine EG541SC

I am playing my black tak in this one.

This is a Takamine G Series EG541SC bought in North Carolina when I was playing in a band called Double Take.

Specs:

Top - Solid Spruce

Back - Nato

Sides - Nato

Finger Board - Rosewood

Electronics - TK40

Finish - Gloss Black

Check out more Takamine G Series Guitars

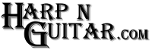

The C harmonica is required in this one.

A C harmonica is the first one you need to follow along with the lessons on the site. I often play a Hohner Special 20 Harmonica in the key of C through a Shure Green Bullet microphone Model 5200 and Fender Super Champ amplifier

The Hohner Harmonica Neck Holder fits harmonicas up to 7-1/2" long.

With a long-lasting nickel-plated finish, this harmonica rack is adjustable and fits any neck shape.

Help File

Music Theory For Harp N Guitar

Music Theory can be used to aid in determining the key and style of a song which can then be used to decide which position to play in. Yeah, we'll go through playing in different positions and how to pick out the correct key harmonica to use.

Music Theory

To define Music Theory, let’s first define music.

Music is the arrangement of notes or tones that occur in a rhythmic fashion.

Music theory is the study of these tones and rhythms and provides a way to communicate what these notes are and the rhythm they are played in. Music theory is also used to explain relationships between notes and why groups of notes sound good together and why certain chord progressions go together better than others.

And why certain key harmonicas work with certain key songs.

Pitch

Tones or notes can be defined by their pitch which is a measurement of the highness or lowness of a sound. The pitch of a note can be measured scientifically by its wavelength or the frequency of air vibrations that occur per second measured in hertz (Hz) or frequency per second.

For example, the standard pitch that all other notes are set in relation to is A above middle C. It has a specific wavelength of 440 Hz. So a note that has a frequency of 440 Hz, we know as the A above middle C.

Naming The Notes

Standard music has been broken into twelve distinguishable repeatable tones that are represented by letter names plus modifiers. The interval between each of these tones is called a semi-tone. Two semi-tones make a whole tone.

Standard music notation uses seven letters, (A, B, C, D, E, F, G), plus the modifiers sharp (#) and flat(b) to name notes.

Most of the unmodified note names have a whole tone between them. The exceptions are between B and C, and E and F. There is only a semi-tone between these notes which can be clearly seen on the keyboard where the black keys represent the sharp and flat notes. There isn’t a black key between B and C or E and F.

One modifier raises the pitch of a note by a semi-tone, the sharp (#), and the other lowers the pitch of a note by a semi-tone, the flat (b).

Here are the twelve repeatable tones of Standard Western music.

A, A# or Bb, B, C, C# or Db, D, D# or Eb, E, F, F# or Gb, G, G# or Ab, then starting at A again. This second A is said to be an octave higher than the first so the twelve semi-tones comprise an octave. This progression of notes a semi-tone apart is also known as the chromatic scale.

Looking at these tones shows us a couple of things.

Between A and B are the notes A# or Bb (A sharp, B flat). These are actually the same notes but with 2 different names. These notes are said to be enharmonic. All modified notes have an enharmonic equivalent. Whether a particular pitch that has an enharmonic equivalent is named by its flat name or its sharp name is dependent on the key signature in which the note occurs.

Enharmonic Notes

A# and Bb

B and Cb

B# and C

C# and Db

D# and Eb

E and Fb

E# and F

F# and Gb

G# and Ab

There is only a semi-tone between B and C so B# or B raised by a semi-tone is actually C. Conversely Cb is actually B. The same goes for E and F. Raising E by a semi-tone, E#, is the same as F. Fb is actually E.

Major Scale and Intervals

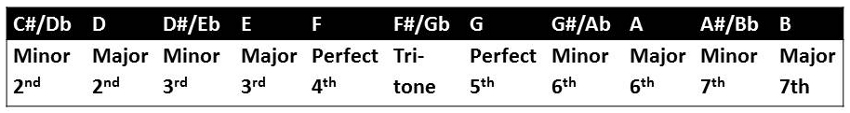

As seen above, the chromatic scale is formed by ascending or descending notes that are a semi-tone apart. Changing the interval between adjacent ascending or descending notes forms different sounding scales. What is known as the major scale, has a certain pattern of semi-tone and whole tone intervals between notes. Different key major scales start on differing notes but the intervals between each note in the scale remains the same. The C major scale consists of the following notes – C D E F G A B C. The interval between the root note, C and the second note D is two semi-tones or a whole tone. This is also known as a major 2nd interval. The interval between D and E is also a whole tone. Between E and F is a semi-tone. Between F and G is a whole tone. Between G and A is a whole tone. Between A and B is a whole tone and between B and C is a semi-tone. All major scales are built on these intervals. The formula is tone – tone – semi tone – tone – tone – tone – semi tone.

C D E F G A B C

1 1 ½ 1 1 1 ½

The interval between the root note, C and the third note E is known as a major 3rd. If E were lowered to Eb, then the interval would be called a minor 3rd. The interval between the root note and the fourth note of a major scale is called a perfect 4th. The interval between the root note and the fifth note of a major scale is called a perfect 5th. If the 5th note were lowered a semi-tone, then the interval is known as a tri-tone. The interval between the root and 6th note is a major 6th. Lowering the 6th note by a semi-tone would make this interval a minor 6th. The interval between the root and the 7th note is a major 7th. Lowering the 7th note by a semi-tone creates the minor 7th interval.

The following table outlines these intervals from starting note, C.

Music Notation

In music, notes have a particular pitch and occur at a particular time. Music notation is used to show this relationship. If you can break music down to specific tones and rhythms, then you can graphically represent and communicate it. That’s what music notation attempts to do – represent a piece of music on a piece of paper so that others can generate the music without having heard it before.

The Musical Staff

Every pitch can be represented in music notation on a series of lines called a Staff.

Above is musical notation representing the C major scale. The five horizontal lines and 4 spaces make up the staff. The ornamental looking G at the beginning is the treble clef. After the clef comes the key signature which denotes which notes will be sharp or flat. In the case of the key of C, there are no sharps or flats and so nothing is shown for the key signature. All other keys do have at least one sharp or flat in the key signature which will become evident when exploring the Circle of Fourths and Fifths. The key signature is followed by the time signature, which in this example is 4/4. Following that are the notes that make up the scale over two octaves. This is divided into four bars or measures represented by the vertical lines.

Clefs

There are different types of clefs which govern the names of the notes on the lines and spaces. The most common are the treble clef above and the bass clef. When the clef is a treble clef, then notes located on the lines are, starting from the bottom, E, G, B, D, F. The spaces represent the notes F, A, C, E.

The circular part of the treble clef circles around the second line. This second line represents the note G. The treble clef is also known as the G clef.

Ledger Lines

If a note extends beyond the staff, then ledger lines are used to expand the normal staff. Note that the first note of the scale above, C, extends below the range of the staff and is represented on a first ledger line. The same also applies to the upper ranges. The last three notes in the example above are placed on ledger lines above the staff.

Key Signature

The key signature tells us which notes are to be played sharp or flat. The key signature occurs right after the clef sign. In the key of C as in the example above, there are no sharps or flats and so the key signature is empty.

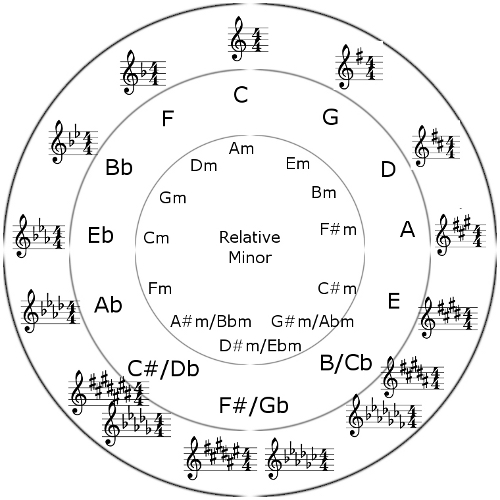

Circle Of Fifths/Fourths

The circle of fifths is a great tool for figuring out key signatures as well as what key harmonica to use. First let’s use it for figuring key signatures.

Starting at the top of the circle is the key of C. Every step going in a clockwise direction is to go up a perfect fifth. G is the fifth note in the C major scale so going from C to G is an interval of a perfect 5th. Travelling clockwise around the circle is the Circle of Fifths.

When going in the opposite or counter-clockwise direction, every step is a perfect fourth interval. Travelling a step counter clockwise from C is F which is the fourth note in the key of C major and so constitutes a perfect 4th interval. When going in this direction, it is the Circle of Fourths.

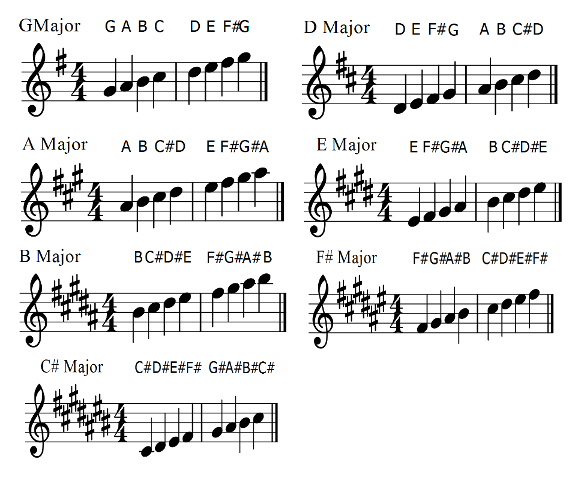

Let’s look at the other keys and their key signatures. Sharps and flats are added to key signatures in a specific way. Every step we go around the circle of fifths, we add a sharp to our key signature. For example, starting with C major that has no sharps or flats and going up a fifth to G, a sharp is added. For the key signature of G, we have one sharp. This added sharp will be the seventh note of the scale. The seventh note of a G major scale is F and so will be sharped, or F#. This sharp is added to the key signature so the key signature of G major has one sharp, F#. This will keep our major scale intervals intact:

G A B C D E F# G

1 1 ½ 1 1 1 ½

Continuing on with this example, the fifth note of the G major scale is D so going from G major to D major we add another sharp, the seventh note of our new key, which in this case is C and so will be C#. We keep the first sharp already added, F#, and add a C# to the key signature, so that the key of D major has two sharps, F# and C#.

Go up to the fifth note of the D major scale lands us on A. For the key of A major we add a third sharp to our key signature which will be the seventh note of the scale or G#. So the key signature for A major is three sharps, F#, C# and G#. Going up a fifth and adding a sharp to our key signature each time we do is referred to as going around the Circle of Fifths. The rest of the sharp key signatures can be found this way.

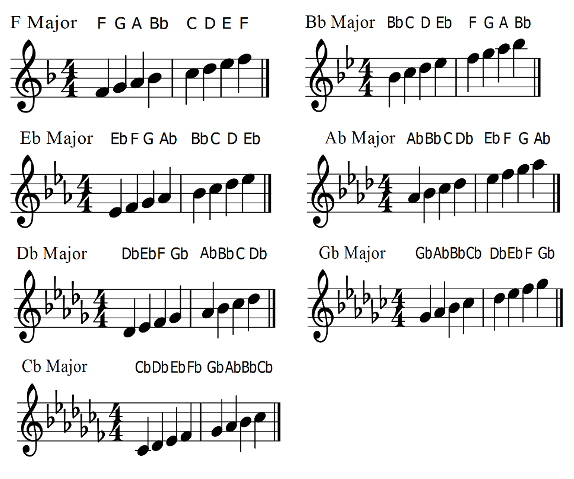

Circle Of Fourths

That covers the sharp key signatures. The flat key signatures are formed by starting at C and going up a fourth or going counter clockwise around the circle. The fourth note in the key of C is F. Going from the key signature of C to F, we add one flat, Bb. The note that is flatted is the fourth note of our new key and so the key signature for F is one flat, Bb.

Starting on F and going up a fourth lands us on Bb. Here we will flat the fourth note, E, and so the key of Bb will have a key signature that has two flats, Bb and Eb.

Starting on Bb and going up a fourth lands us on Eb. The fourth note in the key of Eb which is A is the next flat to be added to the key signature and so the key of Eb has three flats, Bb, Eb and Ab. Continuing around the circle in a counter-clockwise motion is really going around the Circle of Fourths and the rest of the flat key signatures can be determined the same way.

Time Signature

The time signature tells us two things. The top number tells us how many beats there are in a single bar or measure of music. The bottom number tells us which type of note receives a single beat. So in the above examples, there are four beats per measure and a quarter note receives one beat.

Common time signatures include 3/4, 4/4, 6/8

3/4 - three beats per measure, quarter note gets one beat. Eg – waltzes.

4/4 – four beats per measure, quarter note gets one beat. Eg – most rock, blues, country.

6/8 - six beats per measure, eighth note gets one beat. Eg – Gordon Lightfoot’s Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald.

What Key Harmonica Should I Use

We can use the Circle of Fourths/Fifths to help determine which key of harmonica to use.

1st Position – If a song is in a particular major key, then the key harmonica to use will match the song key. If a song is in the key of C major, a C harmonica can be used. This is known as playing in first position and is also known as Ionian mode.

2nd Position – For a blues song you will want to play in second position. The correct key harmonica to play can be figured out by going around the Circle of Fourths. For example, if the song is a blues in the key of C, in order to determine which key harmonica to use, go one step counter-clockwise or up a perfect fourth in key to put you at F. The dominant 7th chord in the key of F is C7. Drawing on holes 2, 3, 4, and 5 on an F harmonica produces a C7 chord which is perfect for blues in C. Each of these notes can also be bent to form other notes that are part of our C blues scale.

If you have a harmonica in a specific key and want to know which key blues it is used for, go one step around the Circle of Fifths or up a perfect fifth from the harmonica key. The C harmonica is good for playing blues in G.

Conversely, if you know which key blues to play and want to know which harmonica to use, go a single step around the Circle of Fourths or up a perfect fourth from the blues key. For G blues, use a C harmonica.

Playing in second position is also known as playing in Mixolydian mode.

3rd Position – This position can be used for playing minor keys. For example, if the key of a song is Am, then looking at the Circle of Fourths go 2 steps from A to get to third position. This gets us to the key of G. A G harmonica can be used to play a song in A minor. The A minor chord on this harmonica is -4 -5 -6 and -8 -9 -10. This puts us in Dorian mode.

4th Position - All major keys have associated relative minor keys. The relative minor scale starts on the sixth note of the major scale. So in the case of C major, the sixth note is A. The A minor scale has the same key signature as C major so if our song is in the key of A minor, then the C harmonica can be used for this. Going four steps around the Circle of Fourths from A lands us on C and so playing in the relative minor key is playing in fourth position.

The Circle diagram also shows the relative minor key for each of the major keys in the inner circle. A real world example would be Bruce Springsteen’s The River. The song is in the key of Em. This is the relative minor of G major and so a G major harmonica can be used for this song. G is the fourth step around the Circle of Fourths from E

4th position is also known as playing in Aeolian mode.

5th Position and Beyond – Continuing around the Circle of Fourths leads to the 5th, 6th, 7th positions and so on but key signatures at this point are so different from the original key that it doesn’t make sense to be playing in these positions.

12th Position – 12 steps around the Circle of Fourths is the same as a single step around the Circle of Fifths. So for the key of C, G is 12th position. Playing in 12th position is not uncommon. The difference in the key signatures between C and G is a single sharp, F#. Playing in C with a G harmonica gets a bright lift from the F#.

12th position is also known as playing in Lydian mode.

5 Pack Case of Hohner Special 20s

What do I like about the Special 20s?

Great Sound, Smooth Comb, Responsive to Bending - but not loose, Affordable. I play Special 20s more than any other model.

Martin Acoustic Guitar Strings

If it's been a while since you've changed your strings, you won't believe the difference in the sound. These are some excellent Martin strings. Need I say more? Totally affordable.

Hohner Harmonica Holder

The Hohner Harmonica Neck Holder fits harmonicas up to 7-1/2" long, has a nickel plated finish and fits any neck shape.

I have used a similar holder for over 25 years. This no-nonsense holder will work for you.

Leave a Reply